[English text below]

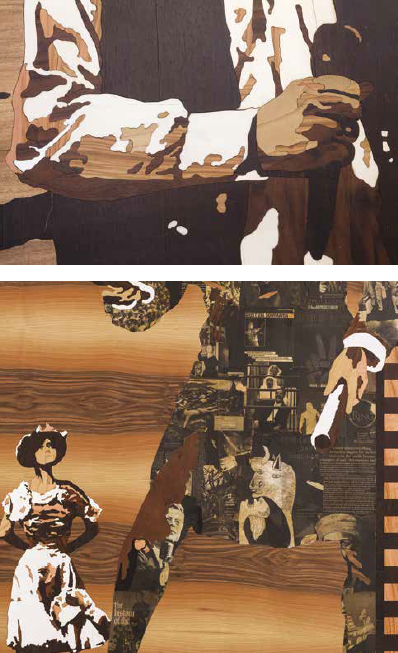

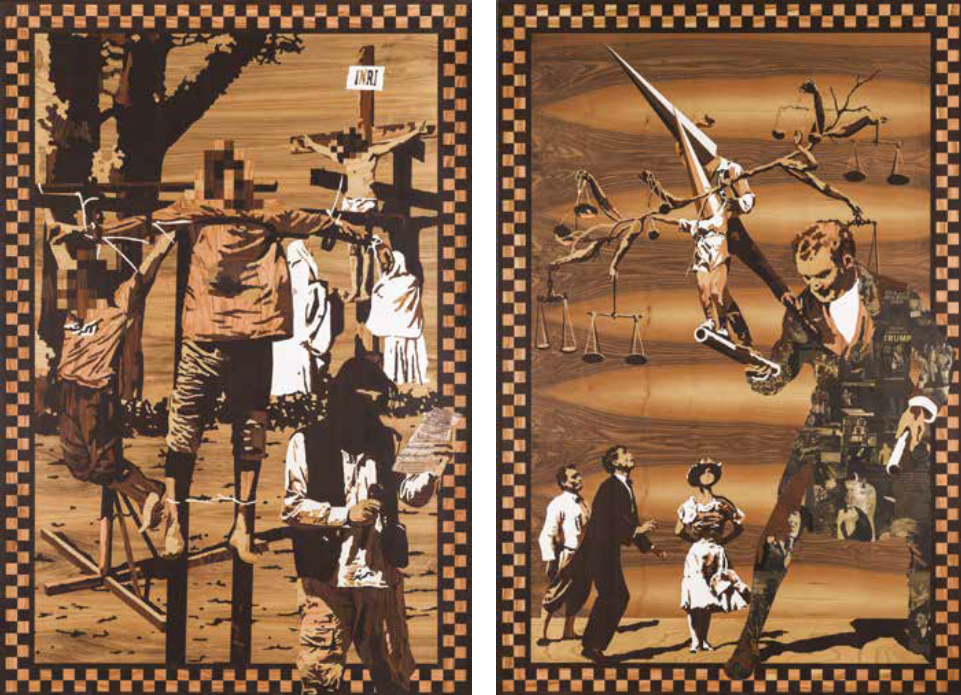

Il legno intarsiato è l’ultima delle tecniche sperimentate dall’artista, che affida il proprio disegno nelle mani dei migliori intarsiatori. Il primo fu un lungo fregio a Ginevra, il secondo una ancor più grande pavimentazione allestita per la Biennale di Lione con sette grandi scene, realizzate tra la fine del 2019 e il principio del 2020. In mostra a Pistoia ne sono arrivate due, incastonate in una pavimento realizzato ad hoc e scelte per mettere al centro due temi cardine della ricerca di Mastrovito: (In)giustizia e Condanna.

Una caratteristica precipua dell’arte contemporanea è l’ambivalenza, se non l’ambiguità, del suo contenuto, l’artista sfugge come un’anguilla la monolettura della propria opera e, figlio dei tempi, si sente a suo agio se lasciato libero di giocare in almeno un paio di campi semantici. Non si tratta solo dei consueti livelli dell’iconologia e iconografia, per intenderci, ma di una dualità necessaria cui negli ultimi decenni ci hanno abituato, per fare qualche nome, gli Young British Artists e il nostro Maurizio Cattelan. L’opera di Mastrovito in che modo partecipa di questa necessità contemporanea, al netto della sua complessità di simboli e della ricchezza di riferimenti che contiene, qui moltiplicata dalle parti in collage? La violenza del soggetto non è celata, il dramma è immediato, il mostro di una giustizia impossibile che ci domina e il dramma di crocifissi che sono ladroni, ma anche torturati di ogni guerra, ci sono sbattuti in faccia senza risparmi. Eppure, la nostra prima (e ultima) impressione, guardando questo pavimento, è lo stupore della bellezza. Ci chiediamo allora se si tratti semplicemente della stessa esperienza che facciamo di fronte, poniamo, ai dannati del Giudizio Universale di Luca Signorelli a Orvieto, in cui la bellezza della pittura (e del corpo) sembra vincere su tutto, o se stia proprio in questa sfrontata piacevolezza la partecipazione di Mastrovito all’ambivalenza contemporanea. È una continua sperimentazione tecnica dove la violenza della vita, dell’uomo come della natura, non riescono a separarsi mai dalla redenzione della bellezza, che sempre ammanta di speranza l’opera di Mastrovito.

Il titolo della serie di intarsi da cui son tratte le scene III e IV, Il mondo è un’invenzione senza futuro, non riesce, infatti, a persuaderci completamente. Il nichilismo che traspare è un’attitudine estranea all’artista quanto una squadra avversa. Come ogni caravaggesco, il suo campo da gioco è sempre la realtà. Il mondo, che dalla finestra ha tirato giù sul pavimento, sarà pure quello violento e ingiusto che conosciamo, ma, proprio perché dannatamente umano, rigetta tanto le scorciatoie estetiche, quanto quelle del nulla teorizzato.

The world is an invention with no future

Inlaid wood is the latest of the techniques experimented by the artist, entrusting his drawings to the hands of the finest inlayers. The first was a long frieze in Geneva; the second an even bigger floor design set up in the Lyon Biennale featuring seven large scenes, produced between the end of 2019 and the start of 2020. In the show in Pistoia, there are other two, embedded in a floor created especially and chosen so as to highlight two of the key themes that emerge from Mastrovito’s research: (In)Justice and Condemnation.

One of the main characteristics of contemporary art is the ambivalence, if not indeed the ambiguity, of its contents. Like an eel, the artist slips away from the single letter of his own work and, as a child of his times, he feels as ease if he is left free to play in at least a couple of semantic fields. It’s not just a matter of the usual levels of iconology and iconography, as it were, but of a necessary duality which we have become accustomed to – to name but a few – by the Young British Artists and our own Maurizio Cattelan. In what way does Mastrovito’s work take part in this contemporary necessity, setting aside its complexity of symbols and the wealth of references that it contains, multiplied here by the parts in the collage? The violence of the subject is not concealed; the drama is immediate, the monster of an impossible justice which dominates us and the drama of crucifixes which are thieves but also the tortured of every war, are thrust in our faces mercilessly. And yet, our first (and last) impression, gazing at this floor, is the awe of beauty.

And so we wonder whether it is simply the same experience that we have, say, before the damned in the Last Judgment by Luca Signorelli in Orvieto, in which the beauty of the painting (and of the body) seems to win over everything, or whether Mastrovito’s participation in contemporary ambivalence lies right here in this bare-faced pleasantness. It’s a continuous technical experimentation in which the violence of life, of man, and of nature are unable to ever detach from the redemption of beauty, which always cloaks Mastrovito’s work with hope.

The title of the series of inlays, from which scenes III and IV of Il mondo è un’invenzione senza futuro are taken, is in fact unable to convince us entirely. The nihilism that it transmits is an approach as extraneous to the artist as an opponent team. Like every Caravaggian, his field is always that of reality. The world, which he has brought down from the window to the floor, may be the violent and unjust world we know, but by virtue of its being so damn human, it rejects both aesthetic shortcuts and those of theorised nothingness.