[English text below]

Così come il Sant’Ippolito ha trovato naturalmente posto al centro dell’esposizione durante la sua progettazione, ci è voluto qualche mese perché un’opera centrale e germinale come Johnny (2006) trovasse in mostra il suo spazio di necessità. Si tratta della più importante videoanimazione dell’artista, da considerare una sua opera “giovanile”, con tutti i pregi e difetti che questo comporta. Quando fu realizzata non era tanto la capacità registica dell’autore ad essere alle prime armi, quanto le tecniche di ripresa e montaggio di un’opera comunque complessa come questa, a non essere di facile dominio pubblico come lo sono oggi. Per un artista in cui la tecnica è così centrale, non appare superfluo chiedersi se avrebbe senso rimettere mano all’opera, forse rifarne completamente il file proiettato, sacrificandone magari la freschezza vintage dal vago sapore VHS, sull’altare di una perfetta leggibilità dell’immagine. Ancora una volta la domanda vale forse più della risposta, da ricercare probabilmente tenendo a mente almeno due episodi cardine dell’arte. Da un lato, il completo rifacimento del celebre Squalo di Damien Hirst (The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living) del 1991, sostituito con un animale nuovo di zecca e a fauci spalancate. Dall’altro, la perdita di un’altra feroce freschezza, quella che ci tocca constatare quando dal trittico Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion di Francis Bacon del 1944, spostiamo gli occhi sulla seconda versione che ne volle trarre nel 1988. Altre storie e altri nomi, per carità, ma i riferimenti servono se alti.

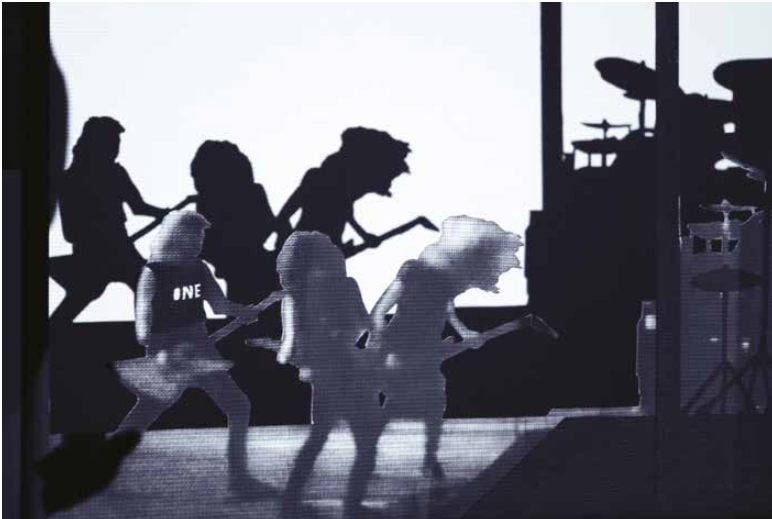

La trama di quest’opera di Mastrovito è quella di E Johnny prese il fucile, il film drammatico di Dalton Trumbo che ha ispirato la canzone dei Metallica One, da cui parte e finisce anche I Am Not Legend. Johnny è un giovane americano che nella Prima guerra mondiale, colpito da una granata, perde braccia, gambe, il volto, le orecchie e tutti i sensi tranne il tatto. Mantenuto artificialmente in vita per anni, a scopo scientifico, giace in un ripostiglio buio ed è perfettamente lucido. L’unico sollievo concessogli è un’infermiera che lo accompagna nel suo trapasso infinito. “Riguardando il mio Johnny mi sono detto: è pieno di sovrastrutture, di livelli di pensiero, di citazioni su citazioni che vengono rimescolate, rimasticate e rivomitate. Praticamente è NYsferatu e I Am not Legend in nuce”. Il Cristo, qui esplicitamente chiamato in causa, si riscopre centrale nella produzione dell’artista e paradigma dell’infilata delle cinque opere che si affacciano su Sant’Andrea: scompaginando con il proprio sacrificio le regole della natura descritte nell’aiuola di libri, dando esempio e ragione al martirio dei santi evocato nella vetrata, interpretando le croci dell’intarsio, e apparendo in trasparenza sotto le braccia stese del Sant’Ippolito-Mastrovito.

Johnny

While Sant’Ippolito found its natural place in the center of the exhibition during the planning stage, it took us a few months to find a satisfactory position for a central and germinal work like Johnny (2006). This is one of the most important works of video animation, to be considered one of his ‘youthful’ works, with all the pros and cons that this entails. When it was made, it was not so much a matter of the artist’s directing skills being in their early days, but rather the techniques of shooting and editing of a work of this complexity were not so widely known and understood as they are today. For an artist who gives such a central role to technique, it does not appear superfluous to wonder if it would make sense to go back and work on it, perhaps completely redo the project file, perhaps thereby sacrificing the vintage freshness with a vaguely VHS taste to them on the altar of the perfect legibility of the image. Once again, the question is perhaps worth more than the answer, to be sought out probably bearing in mind at least two key episodes of art.

On one hand, the complete remake of Damien Hirst’s famous shark (the Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living) in 1991, substituted with a new animal, its jaws wide open. On the other, the loss of another ferocious freshness, that which we need to reckon with when from the triptych three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion by Francis Bacon (1944), we shift our gave onto the second version that he decided to make of in in 1988. Other stories and other names, without a doubt, but references are important if they come from high up.

The plot of this work by Mastrovito is that of Johnny Got his Gun, the dramatic film by Dalton Trumbo which inspired Metallica’s song One, which also opens and closes I Am Not Legend. Johnny is a young American who, in the First World War, after being hit by a grenade, loses his arms, legs, face, ears and all his senses except his touch. Kept alive artificially for years for scientific purposes, he lies in a dark closet room and is perfectly conscious. The only solace conceded to him is a nurse who tries to accompany him in his attempt to die. “Looking back at my Johnny, I said to myself: it’s full of superstructures, of levels of thought, of quotes upon quotes that are all mixed up together, chewed up and spewed out. Basically, it’s NYsferatu and I Am not Legend in a nutshell.” Christ, explicitly called upon to appear here, turns out to be a central figure in the artist’s production, and a paradigm of the series of the five works that look onto St Andrew’s: disrupting the rules of nature laid out in the field of books with his own sacrifice, giving both an example and proof of the martyrdom of saints evoked in the glass panel, interpreting the crosses of the inlay, and appearing transparently below the outstretched arms of St Hippolytus-Mastrovito.